Notes on Debt

A book review of

Book review of Debt by David Graeber

Every so often I deviate from novels and dive into an esoteric part of history. Spending a lot of time with imaginary people and their imaginary lives is fun, but also a sure fire way to lose touch with reality (have you ever had a dream about a person that doesn’t exist but you felt deeply attached to? That’s kinda what reading novels feels like), so I read history. It keeps me sane, sharp and curious. This time I found myself reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 years an extensive treatise on debt, economics, and the origin of money. I’ve written about Graeber before and his book Bullshit Jobs and he’s quickly become my favorite anthropologist for his wit and candor. It’s easy for me to doze off as soon as most academics open their mouths, but Graeber is an exception. He always has something to offer and is never a bore. While reading this four hundred page book I was met with parable after parable. Stories of men getting rich, losing it all, and getting rich again. Men who auctioned off their wives and children due to a bad harvest. Empires rising and falling in the blink of an eye due to infighting and inequality (sound familiar?). Petty squabbles over money and honor. Bar fights that end in lives’ lost. Explorations fueled by riches that end in ruin. The world around humans has changed, but the nature within them has not. Men are still men, and money still kindles many conflicts. I could go on and on about this book and what’s in it, but I’d rather do it justice by talking about some of the more compelling ideas I came across while reading.

The Myth of Barter

What is the origin of money? Ask any decently educated person and they’ll go into a fable involving the trading of seashells or some household commodity for goats. We’re taught that in the absence of a physical currency, our ancestors merely looked around and used whatever was available. Bartering local, easily accessible items for the sake of survival. We’re taught that it’s only from thousands of years of experimentation that we’ve arrived at fiat money, the byproduct of evolution, shaped and formed from the past mistakes of unsystematized shell-based economies. The linear progress of barter to the USD is compelling because it gives us the sense that we’re at the apotheosis of human achievement. Only, it’s not true. Barter and even currencies came much later than the original form of money, debt. Before cash, ingots, shells, or shekels came into play ancient societies used ledgers as a way to capture credits and debts. One of the oldest mechanisms for tracking such debt was a tally stick (hence the origin of the word tally). Back in the day, when one owed a debt, they would split a stick in half and the two halves would represent the creditor’s claim and debtor's dues. It worked because debt hasn’t always been an instrument of the state as we know it today. The earliest forms of debt were generally communal. Neighbors owing neighbors, friends owing friends. This system persisted for so long (and still does to an extent) because debt and money was interwoven into the spirit of everyday life. There were neither banks nor professional lenders to facilitate these interactions. That’s not to say this was an idyllic time. When one couldn’t pay their debts, physical altercations often broke out and could certainly become fatal. But the very nature of debt wasn’t yet a financial instrument that could be used to build and destroy empires, it was a shake of the hand and a tip of the hat. As societies grew and nations emerged, the communal debt keeping system became harder to scale and currencies were created to allow commerce across large geographic boundaries. But even still, for some of the most important transactions (agricultural loans, dowries, fetching your daily bread) the informal credit system thrived.

Thanks for reading Ricardo Pierre-Louis! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

Modern Empire

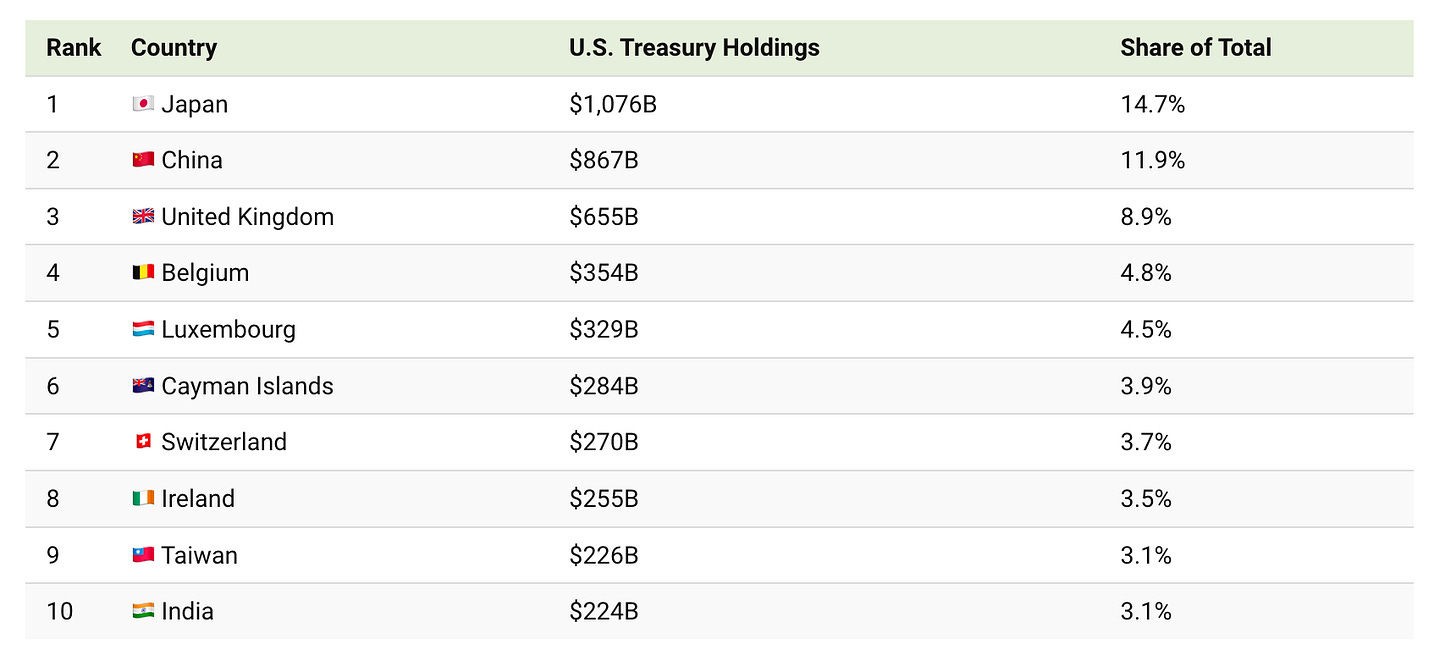

What’s the difference between a man demanding a hundred dollars at gunpoint versus one demanding a hundred dollar loan at gunpoint? Not much, right? This clever metaphor perfectly describes the way U.S. debt works on an international scale. Many smaller nations hold vast reserves of U.S. debt in the form of treasuries. But they also have our military bases stationed at or inside their borders. Below are the largest holders of U.S. treasuries:

You’ll see that the number one holder of U.S. debt is Japan, which up until 2015 was essentially banned from having an army and relied heavily on the U.S. to solve its international conflicts. The U.S. has eighty-five bases across 77,000 acres of land within Japanese borders. This means that no matter how much debt Japan incurs it’s unlikely (if not impossible) for them to actually collect on it. The U.S. empire operates this way all around the world. We put bases and drones around the world, load countries with our debt, and if they object, well that’s what the military is for. The perceived value of our economy is largely based on the perceived threat of violence. Of course it’s unlikely we’ll go to war with Japan or any other country in the interim for debt anytime soon, but as long as the threat is there, it’s enough to keep anyone from trying to collect.

Debt Explosion

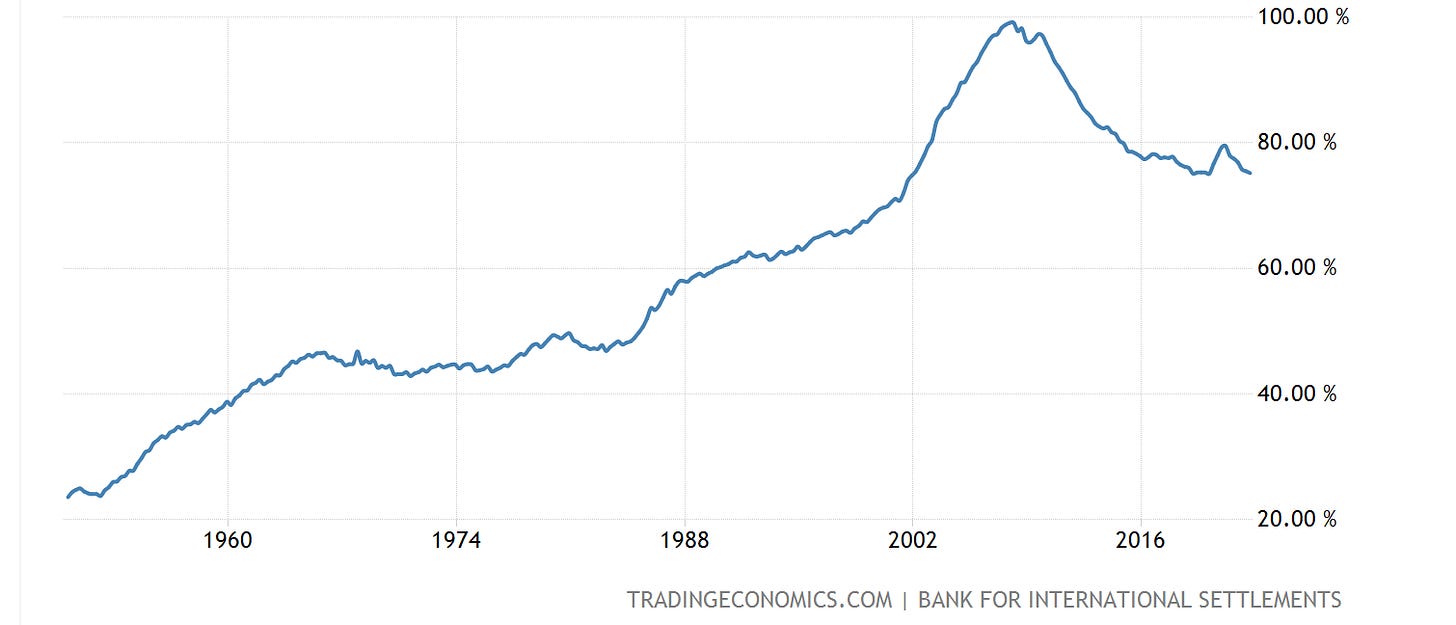

The volume of consumer debt loaded onto the average consumer has exploded in the last few decades. Within the last fifty years we’ve seen the creation of student loans (college was free before Reagan), subprime mortgages, legalized usury (payday loans), and a massive increase in medical debt. The average American now has more debt than anyone else in history despite also living in the wealthiest nation in history. It’s not too different from debt peonage or slavery during the medieval times. In fact, there’s a case to be made that peasants in the feudal period had better working conditions than today because they didn’t work nearly as much as most people do now. Ask the average young person and they’ll explain that they have no prospect for homeownership (another form of debt), because they’re being crushed under their existing obligations. Many older folks have no aspirations of retirement and can at best expect to work in a job that isn’t overtly abusive. It’s a bleak picture that has no immediate end in sight, but that’s not to say we can’t be hopeful.

Future Economies

Mark Fisher wrote “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of capitalism.”

It rings true for many of us because we’ve financialized every part of our existence: love, attention, community. There’s very little left of our universe that hasn’t been corrupted by the glooms of commerce. But even though this is the system we have, it’s very unlikely that it will be the system forever. Right now we’re mere peasants looking up at the throne, and saying god grant me a solution in the next life as there can be none in this one. But as the kings disappeared, so will capitalism and all it entails. Interestingly there’s a historic basis for this. It’s well documented that many Indigenous societies often operated by the Marxist principle “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” Tribes worked together and gave out supplies to those that needed it, rather than those who could afford it. These were communal, matriarchal times when we provided for one another without asking “well, what can you do for me.” It’s a system that existed well before modern capitalism, and only disappeared due to the violence of colonization. Its resurgence is possible.

Historically, whenever the lower classes have been overburdened with debt there were jubilees where all slates were wiped clean and debt was forgiven. These ceremonies were overseen by kings largely to keep economies functional and limit bloody conflicts. Now we’re starting to see a resurgence of these jubilees. There’s been a widespread campaign to forgive student loan debt, we’ve even seen Biden pass a limited measure (with opposition from the white nationalist party of course), but it’s an idea that has gained traction. We can expect to see more of these types of measures for erasing debt as it continues to overwhelm us. We have no other choice. If we embark on this same path of overloading folks with debt and take away all their prospects for financial freedom, then our situation will become increasingly untenable.